Bruised and Abused

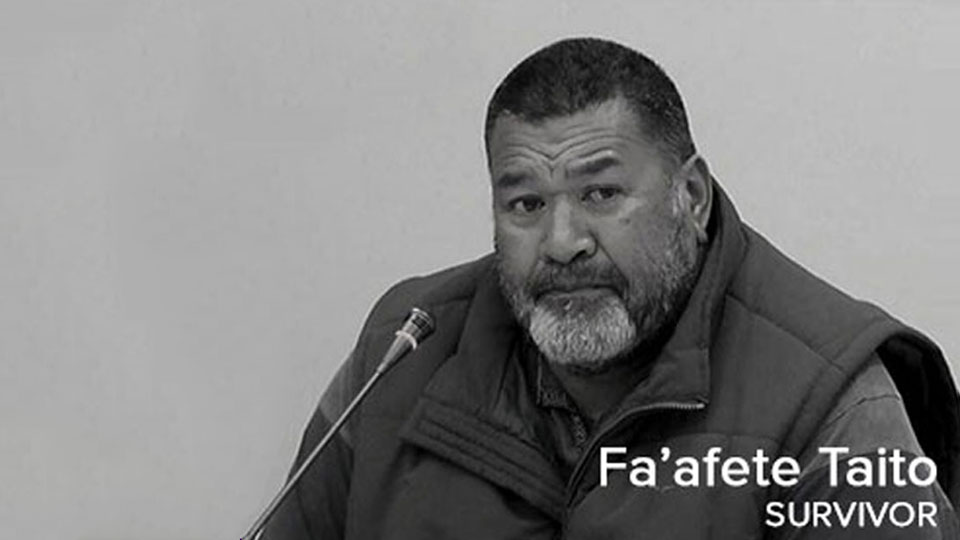

Between 1950-1999 there were Pasifika people who were abused when in the care of the State or faith-based institutions. In response, the Royal Commission of Inquiry Abuse in Care was established to investigate this abuse. Abuse that took place in foster care, police custody, schools or special schools, disability care or facilities, youth justice placement or at a health camp. Among those in care was Fa’afete Taito, a Samoan boy who grew up institutionalised, but willing to share his ordeal for others to learn from.

In the 1950s Fa’afete Taito’s parents moved from Samoa to New Zealand in the hope they could provide a good life and education for their children, enough to be able to send money to family back in Samoa.

Along with three older sisters and one younger, they were raised by their parents, who were very involved with the Church, attending every Sunday and helping out afterwards.

He had a loving Mum and was always close with her.

But his father, like many Samoan men of his generation, struggled with the broader cultural forces at play and the challenges of trying to raise his family in New Zealand society while maintaining Samoan values. He experienced strict discipline at home when he was younger.

At age 12, Fa’afete started running away from home.

He could tell when his father was in a bad mood and he was in for a hiding. As the only boy, he received more hidings than his sisters.

“My Mum would make me kneel in front of my Dad to apologise. He would get the leather belt and beat me until I had giant welts all over my body,” he recalls.

“Mum would try to protect me by covering me with her body and asking my Dad to stop.

“Sometimes he would, but most of the time he would carry on, with Mum copping a few belts as well.”

This pattern of Fa’afete being beaten by my father, running away, and then being beaten upon return, continued. The social workers (and Police) who returned him refused to believe his version of extreme beatings he received. Eventually, he was brought before the Children’s Board in Auckland.

The judge would lecture him, saying that truancy is bad, education is good and that he must learn to stay at home and go to school.

But he became more violent and was getting into fights with other kids.

“Looking back, I suppose I thought violence was normal because of the regular hidings I was getting at home.”

At age 14 he was sent to Owairaka (Boys Home) for the first time.

At a court case which his older sister attended, she read the court file which stated that Fa’afete had been adopted. He never knew, and asked her if it was true? She replied, yes and appeared annoyed that he had never been told.

“My biological mother was my father’s whangai sister, but she gave birth to me out of wedlock and was sent from Samoa to New Zealand before she gave birth,” he recalls.

“My adoptive father informed her she would be leaving the baby with them and would return to Samoa to finish her nursing studies. Later in life, she told me how much this pained her to leave me behind.”

At Owairaka, Fa’afete learned how to steal cars, pick locks and was introduced to cannabis.

He experienced a lot of physical violence, where workers allowed kids to bully and assault other kids. The weak became slaves to the bigger boys and seeing fights appealed to their sense of humour as entertainment.

One day the kingpin attacked him in the activities room, hitting Fa’afete over the head with a Table tennis bat with an officer sitting right there.

“At first I didn’t fight back because I wasn’t sure what would happen if I did,” he recalls.

“I saw the officer sitting there, smiling and watching. I then realised I needed to look after myself. So I fought back. It was only when I was on top of the other boy that the officers pulled me away.”

At the eligible age to attend secondary school, the majority of neighbouring schools wouldn’t take him and he stayed in a foster home.

One of the foster homes was a half-way house for adult prisoners coming out of jail. There were a number of gang members who lived there. Fa’afete would hang around them and, in time, became friends with them.

“I got a few hidings, then got kicked out of high school for burglary when I was 14.”

At that time, it was illegal to suspend or expel kids from school who were under 15. In 1976 the Education Act was amended and he became the first child under the new legislation to receive an exemption order.

“I had a letter I kept with me in case I was stopped by authorities to show that I did not have to be at school.”

Fa’afete also had two stints at the borstal youth prison in Waikeria.

“That was a whole other level to what I had experienced at Owairaka,” he remembers. “In Waikeria, I met a lot of the kids that had been in Owairaka with me. The majority of them had joined the Mongrel Mob and Black Power. A mate of mine who was at Owairaka with me, asked if I wanted to prospect for the Mob. But I heard that a new gang, King Cobras (KCs) had started up in Ponsonby which was my hood, so I wasn’t sure about joining the Mongrel Mob or keen on the bulldog or the sieg heil call.”

Fa’afete said he’d think about it.

While Waikeria was much more violent, he says Owairaka was worse because it created the pathway he was set upon.

“I look back and see the state gifted me the gang lifestyle. In between custody, I was spending a lot of time on the streets with other kids who were in similar situations to me,” he says.

“We would find abandoned houses to stay in until the Police J-team came after us. For a while we crashed at a house in Ponsonby which was next door to the Polynesian Panthers. So I got involved with them, delivering pamphlets.”

Fa’afete met many good leaders at the Panthers. But life was still a struggle.

“In winter, we’d stay under Grafton Bridge with cardboard boxes under us to sleep on. We pinched blankets from Auckland Hospital to stay warm. I was 16 when I started hanging out with others in Ponsonby who would become part of the King Cobras, the KCs,” he says.

“I joined at the end of 1978 and was then sent to do my first lag at the ‘Rock’ (Mt Eden prison) in 1979, I was 17 years old and a fully patched member of the King Cobras.”

More than a decade later, Fa’afete Ieft the gang in 1991 and concentrated on life as a career criminal as he knew no other pathway because this was his normal.

“The criminal underworld and lifestyle became part of who I was. I could not see any other life for me. A lot of the boys who were in the boys’ homes with me had established seniority in the hierarchy of the major gangs. This made my criminal dealings easier because I had such a strong network of connections stemming directly from our time together at Owairaka,” he says.

“They knew me and would deal with me because of that trust and shared understanding. I continued my life of crime and was completely immersed in Auckland’s criminal underworld.”

Fa’afete did a seven-year stint in prison, getting out in 2000 before serving eight years imprisonment at Paremoremo in 2001 for drug offending.

“I served those at Paremoremo prison in Auckland and got out in 2006. By 2009 I knew I had to walk away from the criminal world altogether.”

By then Fa’afete had been using ‘P’ for ten years.

After much deliberation and soul searching with his partner, he made the decision to get out.

“She had been by my side throughout our 29 years and I wanted to be around and live my life with her and between us, our six children and our many mokopuna,” says Fa’afete.

“But it was incredibly hard coming off drugs with no money or support. I lived with my sister, who was unwell, so I also had to take care of her. It took me 10 months to get over the ‘p’ withdrawal symptoms.”

Fa’afete eventually recovered in 2010. But his partner was wary of him going back to his old ways, saying he needed to do something with his time.

He applied for a bridging course at the University of Auckland. It was the beginning of a new academic career. He has now completed a Bachelor of Arts at the University of Auckland with a double major in Sociology and Māori.

With time, and through his studies, Fa’afete says he has had the opportunity to reflect on his life and make peace with his adoptive father.

Fa’afete’s hopes for the Inquiry

“It’s important those from the Pasefika community are involved with this Inquiry. I can speak as a Samoan man, but there are many others, including women and those from other Pacific Islands, who have stories to tell as well. Some people of Pacific heritage can be too deferential towards New Zealand. Although it is true that this country has offered many opportunities and a better life for some of our people, this doesn’t mean we cannot speak out about what has happened. I remember during the dawn raid area (early-to-late 1970s) some families blamed other families and thought it was their fault for not having up-to-date visas. Their sentiment was that “this country has been good to us, so we should be good.”

While it’s true to some extent, he says it can’t excuse the actions of the New Zealand government then who, at times, targeted Samoan and other Pacific Island communities through racist and exploitative policies and practices. It should not be forgotten that it was the NZ government that encouraged Pacific people to migrate here on (limited a work visa) post-war to work in the mainly labour intensive related jobs i.e., manufactories, container wharfs and ignored the visa expiry date so they could keep working. However, when the jobs started to dry up in the 1970s and Pacific people started to be seen as becoming a burden on the welfare system, the NZ government introduced the ‘dawn raids’.

“Our people came to New Zealand and worked hard in factory jobs that New Zealanders didn’t want, only to then be subjected to discrimination and racism,” he says.

“Being part of this Inquiry does not bring shame on me or my family. It’s a way of explaining how the state failed us and the devastating impact it had on our families, communities and society.

“I’m speaking out in the hope that others will feel that they can come forward and share their stories. New Zealand needs to hear the truth about what happened during those years, so we can begin to heal and move forward.

Royal Commission of Inquiry into Historical Abuse in State Care – Need to Know

- The Inquiry is also looking at the abuse that occurred in a faith-based setting such as a religious school or church camp.

- Part of its investigation is considering the impact of the Dawn Raids and the Citizenship Act on our communities.

- The Royal Commission would like to hear from representatives from all our Pasefika nations.

- Talking with the Royal Commission is a unique opportunity to give voice to Pasefika survivors and their journey.

- The Royal Commission understands that these stories are hard to tell. If you want to share your story, its Pasefika Engagement team can work with you, your aiga/family or with organisations that you may be involved with to talanoa about how we can best support you to tell your story.

- Helping the Royal Commission learn about what you went through in care and the affect it had on your life, aiga/family and community, will help us make it safer for Pasefika children in care today.

The Royal Commission encourages survivors or their aiga to call us on 0800 222 727 or email us on contact@abusiencare.org.nz to find out more about the Inquiry. Its website is www.abuseincare.org.nz.

Pasefika Proud is a Pacific response to focus on community-led solutions that harnesses the transformative power of traditional Pacific cultural values and frameworks to encourage violence-free, respectful relationships that support Pacific peoples to thrive and to build strong resilient families.